Typically, in the UK, lacrimal dilation and irrigation are performed in hospital. However, with a little practice and care, it is a relatively simple

procedure for any optometrist or GP to carry out. The equipment required is inexpensive and easily obtained (see Appendices I and II).

This paper will review the relevant anatomy and physiology, discuss the aetiology and evaluation of epiphora (watery eye), and then explain

dilation, syringing and the various dye tests associated with investigating the lacrimal drainage system.

Typically, in the UK, lacrimal dilation and irrigation are performed in hospital. However, with a little practice and care, it is a relatively simple

procedure for any optometrist or GP to carry out. The equipment required is inexpensive and easily obtained (see Appendices I and II).

This paper will review the relevant anatomy and physiology, discuss the aetiology and evaluation of epiphora (watery eye), and then explain

dilation, syringing and the various dye tests associated with investigating the lacrimal drainage system.

|

ANATOMY OF THE LACRIMAL

DRAINAGE SYSTEM

ANATOMY OF THE LACRIMAL

DRAINAGE SYSTEM

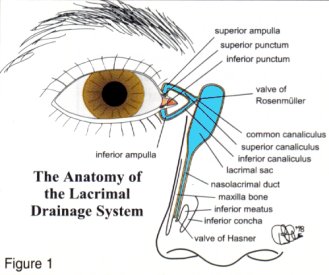

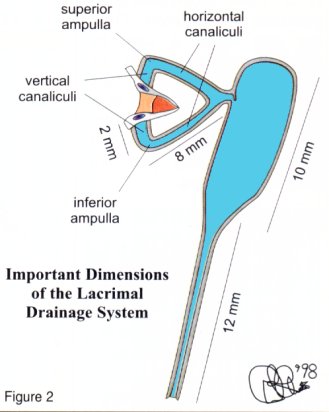

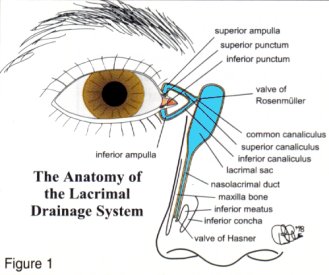

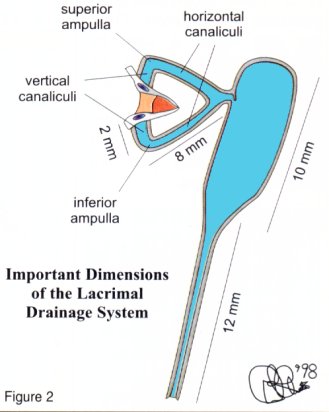

The anatomy of the complete

system is shown diagrammatically

in Figure 1. Some important

dimensions appear in Figure 2.

a) Puncta

One punctum is present at the

medial end of both the superior and

inferior lid. They are situated on

slight elevations called the lacrimal

papillae and face posteriorly so it is

necessary to evert the medial lids to

inspect them. Malposition or

stenosis (narrowing) of the puncta

may cause epiphora.

b) Vertical canaliculus

This is about 2mm long and joins the

horizontal canaliculus at a right

angle called the ampulla.

c) Horizontal canaliculus

This is about 8mm long and usually

joins its fellow to form the common

canaliculus which immediately

enters the (naso)lacrimal sac

through the Valve of Rosenmuller

(flap of mucosa to prevent reflux).

d) (Naso)lacrimal sac

This is about lOmm long and funnels

into the nasolacrimal duct.

|

|

e) Nasolacrimal duct

This is about l2mm long and opens

into the inferior nasal meatus, lateral

to the inferior turbinate (concha). The

Valve of Hasner closes the opening.

f) Valves

About seven other valves have been

described within the nasolacrimal duct

besides those of Rosenmuller and

Horner (see Last) but they have no

valvular function and are usually

ignored. |

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LACRIMAL

DRAINAGE SYSTEM

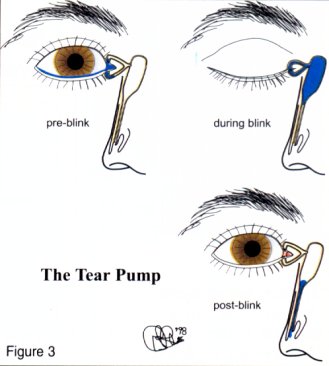

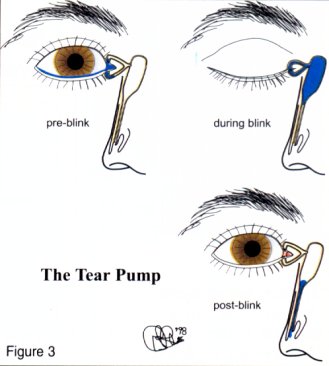

Capillarity ensures that 70% of the

tears enter the inferior canaliculus and

30% through the superior (Figure 3 -

pre -blink). On blinking, the

attachment of the preseptal orbicularis

muscle helps create positive and

negative pressure in the lacrimal sac

which sucks the tears into it (Figure 3

- during blink). This is called the tear

pump. Gravity then helps keep the sac

empty (Figure 3 - post-blink).

AETIOLOGY OF EPIPHORA

Epiphora may be due to a

hypersecretion of tears as occurs when

a foreign body irritates the cornea.

Paradoxically, it may also be due to an

underlying dry eye problem which, in

turn, causes a foreign body reaction

and tearing. Likewise, it may be due to

a lacrimal pump failure as in ectropion

when tears are no longer able to enter

the punctum. It may also be caused

by punctum plugs or punctum

cauterisation for the treatment of dry eye.

|

|

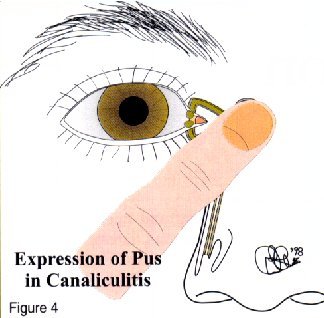

| EVALUATION OF EPIPHORA

a) General inspection

Inspect the lids to see if they and/or

the puncta are poorly positioned.

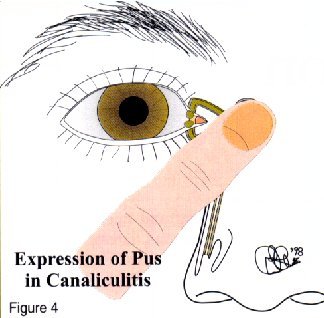

Palpate the lacrimal sac to determine if

it is enlarged due to dacryocystitis or a

mucocele. Compression may cause a

reflux of mucopurulent matter (Figure

4). Pain suggests dacryocystitis.

|  |

b) Slit lamp examination

Inspect the puncta for poor

position, narrowing or blockage

- pouting suggests canaliculitis.

A high marginal tear strip may

indicate epiphora. If fluorescein

is instilled in the conjunctival

sac, it should disappear within

two minutes - retention

suggests there is a problem with

lacrimal drainage. |

|

c) Irrigation

|

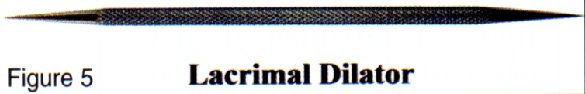

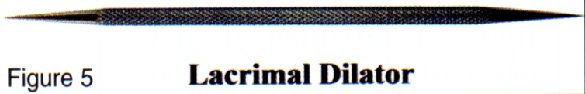

1) Lacrimal dilation

Several types of dilators are

available, for example the

double-ended stainless steel

type in Figure 5 ( see Appendix I) or those incorporated in

punctum plug inserters. Their

use may effect a cure by

releasing mucous plugs or

concretions. Dilation may

produce temporary relief in a

case of stenosis of the punctum.

Lacrimal dilation is also used

prior to inserting punctum

plugs and syringing.

- Wash your hands.

- Some practitioners may

wish to put on surgical

gloves.

- Instil a drop of anaesthetic

on the inferior punctum.

- Sterilise the lacrimal

dilator with a Medi-Swab.

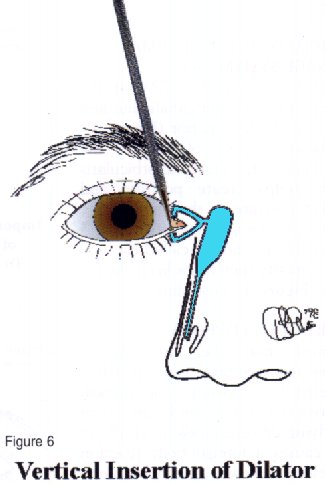

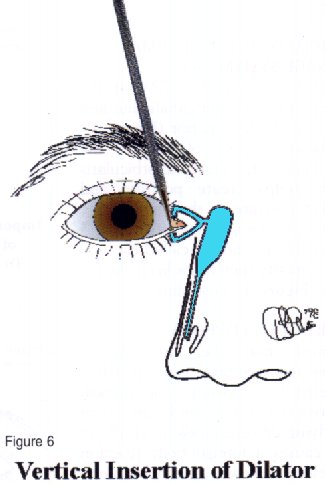

- Insert the dilator vertically

downwards up to 2mm

whilst gently rotating

clockwise and anticlockwise (Figure 6).

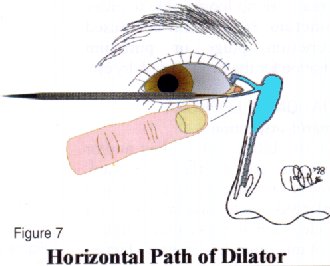

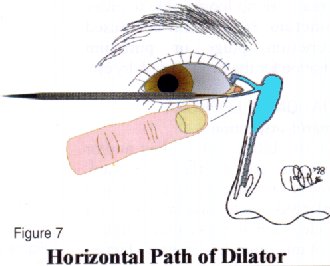

- Pull the lower lid

temporally to straighten

the ampulla and line up

the vertical and horizontal

canaliculi (Figure 7).

- Rotate the dilator

horizontally and insert the

dilator as required.

|

2)Lacrimal syringing

As well as irrigating the

lacrimal system, syringing may

be necessary to dislodge intra-

canalicular punctum plugs.

Procedure

- Wash your hands.

- Some practitioners may wish to put on

surgical gloves.

- Dilate the punctum and canaliculus (see

under 'lacrimal dilation').

- Open the sterile packets of disposable

syringe and cannula and connect them

together.

- Remove the plunger and fill the syringe

with sterile saline.

- Re-insert the plunger, and with the

syringe pointing upward, squeeze out any

remaining air together with some saline.

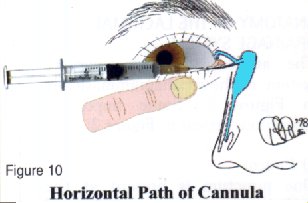

- Insert the cannula into the vertical

canaliculus.

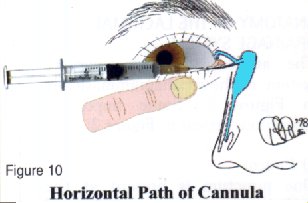

- Pull the lower lid temporally to straighten

the ampulla and line up the horizontal

canaliculus. Rotate the syringe

horizontally whilst inserting until a 'hard'

or 'soft' stop is felt (see over), then pull

back about 2mm (Figure 10).

- Press slowly and gendy on the plunger.

- Ask the patient to report when they

taste saline or feel it in their nose.

|

|

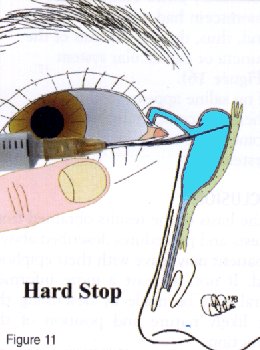

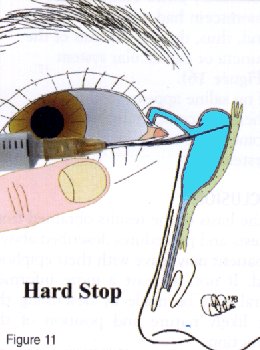

| Hard stop

If the cannula touches the medial

wall of the lacrimal sac and lacrimal

bone, a definite end point is reached.

This is a 'hard stop' (Figure 11) and

indicates that there is no complete

obstruction in the canalicular

system. |  |

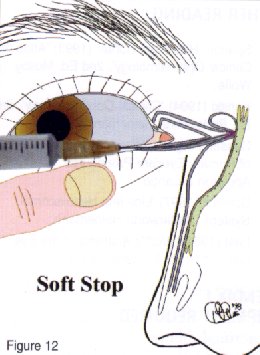

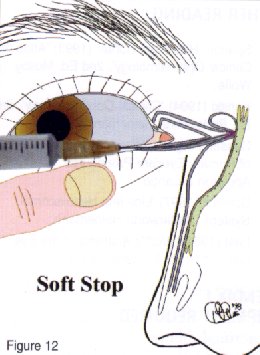

| Soft stop

If a spongy end point is felt, this is

termed a 'soft stop' (Figure 12) and

indicates that the cannula has been

prevented from entering the lacrimal

sac. Therefore, there is a blockage in

the canalicular system and there will

be no distension of the lacrimal sac

when the plunger is pressed.

|  |

Detailed diagnosis

from lacrimal syringing

- If saline refluxes from the inferior

canaliculus, the blockage is there.

- If saline refluxes from the superior

canaliculus, the blockage is in the

common canaliculus.

- If saline passes into the nose, the

problem is hypersecretion of tears or

failure of the lacrimal pump or partial

obstruction of the nasolacrimal system.

- If saline does not reach the nose, there

is a total obstruction of the

nasolacrimal duct and saline may

appear from the superior punctum - the

saline may be purulent if infection is

present - and the lacrimal sac may be

distended.

- An attempt may be made to close the

superior punctum with a dilator or

cotton bud and a further effort made to

clear the obstruction.

|

| Functional obstruction

Sometimes, the lacrimal drainage system

may appear patent when syringing proceeds

uneventfully. However, there may be a

functional obstruction. This means that

under the low-pressure circumstances of

normal tear drainage, all or part of the

lacrimal pathway may collapse. Jones dye

tests may be used to distinguish between

patent systems and functionally blocked

ones. |  |

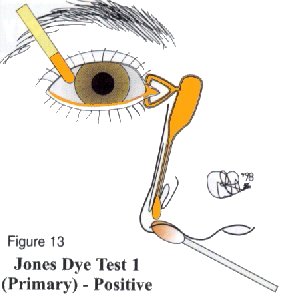

JONES DYE TESTS

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY

Procedure

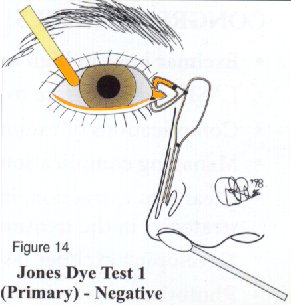

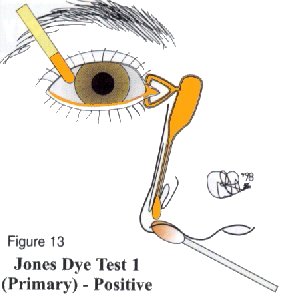

- Instil one drop of fluorescein into the

conjunctival sac (Figure 13).

- Put a cotton bud soaked in anaesthetic

in the inferior meatus.

- If fluorescein is detected after five

minutes, the system is patent (positive

Primary Jones Test).

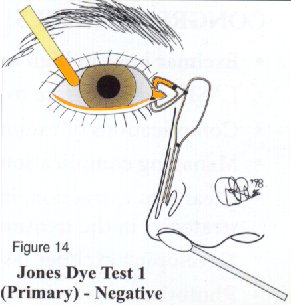

- If no fluorescein is discovered, this

is a negative Primary Jones Test (Figure

14) and the functional obstruction

could be anywhere from the punctum

to the Valve of Hasner.

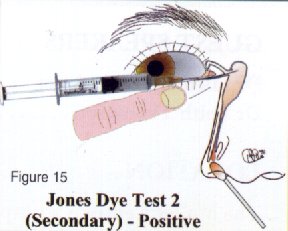

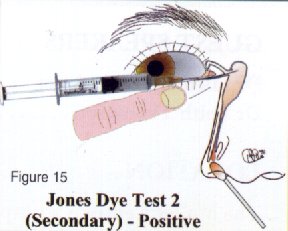

- Next, wash the excess fluorescein from

the conjunctival sac and syringe. If

fluorescein is detected, then this shows

it had entered the sac and constitutes a

positive Secondary Jones Test (Figure

15) and suggests a functional

obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct.

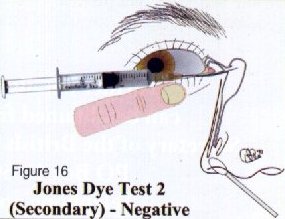

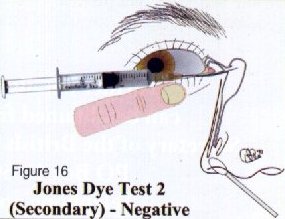

- If no dye is found on the cotton bud

after syringing, this is termed a negative

Secondary Jones Test, because

fluorescein had not entered the sac

and, thus, there is stenosis of the

puncta or canalicular system

(Figure 16).

- If no saline appears in the nose,

there is a complete obstruction

somewhere in the lacrimal drainage

system.

|

|

| CONCLUSION

On the basis of the results obtained from

the tests and procedures described above,

the patient may leave with their epiphora

cured. If not, at least a more informed

referral may be made by describing the

most likely nature and position of the

obstruction.

FURTHER READING

- Spalton, Hitchings, Hunter (1993) 'Atlas of

Clinical Ophthalmology'. 2nd Ed, Mosby

Wolfe.

- Kanski (1994) 'Clinical Ophthalmology'. 3rd

Ed, Butterworth Heinemam.

- Casser, Fingerat, Woodcome (1997) 'Atlas

of Primary Eyecare Procedures'. 2nd Ed,

Appleton & Lange.

- Schmidt (1997) 'Lids and Nasolacrimal

System'. Butterworth Heinemann.

- Last (1961) 'WoIft's Anatomy of the Eye

and Orbit'. 5th Ed. Lewis & Co.

APPENDIX I

EQUIPMENT REQUIRED

- Lacrimal dilator

- Disposable lacrimal cannulae

- 3 or 5m1 disposable sterile syringes

- Anaesthetic drops, e.g. Ophthaine

- Tissues

- Aerosol bottles of sterile saline

- Disinfection for the dilators, e.g

- Medi- Swabs

- Surgical gloves?

APPENDIX II

SOME EQUIPMENT SUPPLIERS

John Weiss, 89-90 Alston Drive,

Bradwell Abbey, Milton Keynes

MK13 9HF

Tel: 01908-318017 Fax: 01908-318708

Castroviejo Lacrimal dilator

#0105040 BI 15

Lacrimal cannulae 0108142 7276

Optimed, Alveston House,

11 Broad Street, Pershore

Worcs, WR10 1BB

Tel: 01386-561845 Fax: 01386-555177

Irrigating Lacrimal Cannula

260 Code No.1276

Wilders Lacrimal Dilator 13-071 |

Typically, in the UK, lacrimal dilation and irrigation are performed in hospital. However, with a little practice and care, it is a relatively simple

procedure for any optometrist or GP to carry out. The equipment required is inexpensive and easily obtained (see Appendices I and II).

This paper will review the relevant anatomy and physiology, discuss the aetiology and evaluation of epiphora (watery eye), and then explain

dilation, syringing and the various dye tests associated with investigating the lacrimal drainage system.

Typically, in the UK, lacrimal dilation and irrigation are performed in hospital. However, with a little practice and care, it is a relatively simple

procedure for any optometrist or GP to carry out. The equipment required is inexpensive and easily obtained (see Appendices I and II).

This paper will review the relevant anatomy and physiology, discuss the aetiology and evaluation of epiphora (watery eye), and then explain

dilation, syringing and the various dye tests associated with investigating the lacrimal drainage system.

ANATOMY OF THE LACRIMAL

DRAINAGE SYSTEM

ANATOMY OF THE LACRIMAL

DRAINAGE SYSTEM